MEDIA

Review: Art Cinema and India’s Forgotten Futures byRochona Majumdar

www.hindustantimes.com | February 4, 2022

Rochona Majumdar charts the trajectory of art cinema in the country through the work of three filmmakers from Bengal – Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen and Satyajit Ray.

Art cinema is a much debated and often misunderstood term. Filmmakers are increasingly cautious about such coinages fearing that it might limit audience access and endanger the economic prospects of their films. Certain characteristic features that became synonymous with art cinema in India could include its slow pace, narrative treatment, choice of subject matter, selection of actors and their style of performance. In many ways, the term helped to identify a kind of film practice that defied the demands of the mainstream or the blockbuster film. Over the years, art cinema has also segued into multiplex cinema of a certain kind which caters to a class – urban, elite, English-speaking and upwardly mobile.

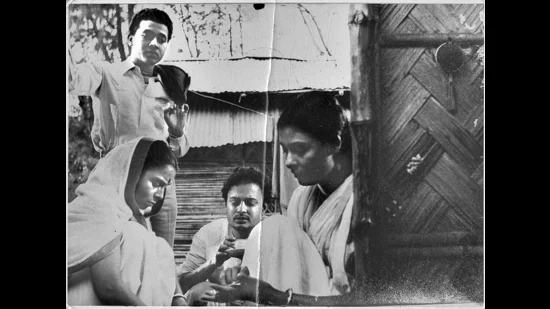

The foundations of art cinema in India were however very different. In her new book Art Cinema and India’s Forgotten Futures – Film and History in the Postcolony, Rochona Majumdar charts the trajectory of art cinema in the country. In the second half of the book, she furthers this conversation through a selection of three filmmakers from Bengal – Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen and Satyajit Ray, hailed by many as the holy triumvirate of an avant-garde sensibility in Indian filmmaking. This could also be seen as an extension of Majumdar’s former academic work which focusses on Bengal. In her introduction, Majumdar also mentions that while the history of popular Indian cinema, or Hindi cinema to be specific, is fairly well documented with a section of academia and mainstream publishing churning out histories of popular cinema through star biographies and monographs on films, amongst other paraphernalia, the same courtesy is not extended to art cinema.

Having said that, one can’t help think that the sustained attention paid to art film luminaries such as Ray, Ghatak and Sen has also eclipsed the works of several other filmmakers from Bengal such as Tapan Sinha and Tarun Majumdar; both important filmmakers who enjoyed commercial as well as critical acclaim. Their films haven’t received the kind of serious critical attention that they deserve. Are we too comfortable in academia to probe beyond the avant-garde mainstream? Majumdar also identifies this shortcoming and hopefully this observation will inspire other scholars and film writers to explore the work of several other filmmakers. After all, the history of art cinema in India, or for that matter any history, is not a monolith. To do justice to the many histories, our ambit has to extend beyond Ray, Ghatak, Sen and even Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Adoor Gopalakrishnan et al.

Art cinema, as is popularly known, thrived on state support. This is often interpreted as the role of the state in trying to create good, realistic cinema or benchmark standards for good cinema. This also begets the question – is all art cinema good cinema? Is experimentation necessarily progressive? We could all benefit from a critical history of art cinema which evaluates films through their content. While art cinema introduced a new aesthetics for filmmaking in India, its influences were primarily European. Many of these films also struggled to merge their European influences with an Indian setting and storyline, often appearing very disjointed. European experimental cinema, lest we forget, came out of a very specific context.

Majumdar dedicates a chapter to the film society movement which played a major role in spreading art cinema in India. She also says that these film societies acted as gatekeepers or purveyors of good taste by showing films which were labelled as intellectual. Besides, the book also mentions the role of critics and opinion makers like Marie Seton who turned Satyajit Ray into an emblem of Indian art film. The elitism of Indian art cinema, like other niche art forms, is undisputable. While the makers claimed that their films were rooted in the real or represented the marginalized and the oppressed, the same sections had scarce or almost no access to these films. The lives of the filmmakers were also vastly different from the subjects of their films. Audiences primarily comprised urban intellectuals or foreign film festival viewers. In fact, it was often said that these films were made for foreign film festivals. The binary between popular and art cinema is dated and a false one, so to speak.

Also, the filmmakers who championed the art cinema movement in India were primarily men from similar class and caste backgrounds, furthering the movement’s extreme elitism. I wonder about the expected reader of this book. There are no new discoveries in it for those familiar with Indian art cinema. Would Columbia University Press have published this book if it had been written by a lesser-known Indian academic?

- Prof. Kunal Ray, Assistant Professor – English Literature.