Ruling a Country 20 Times Larger: The British and the idea of ‘Gazetteers’

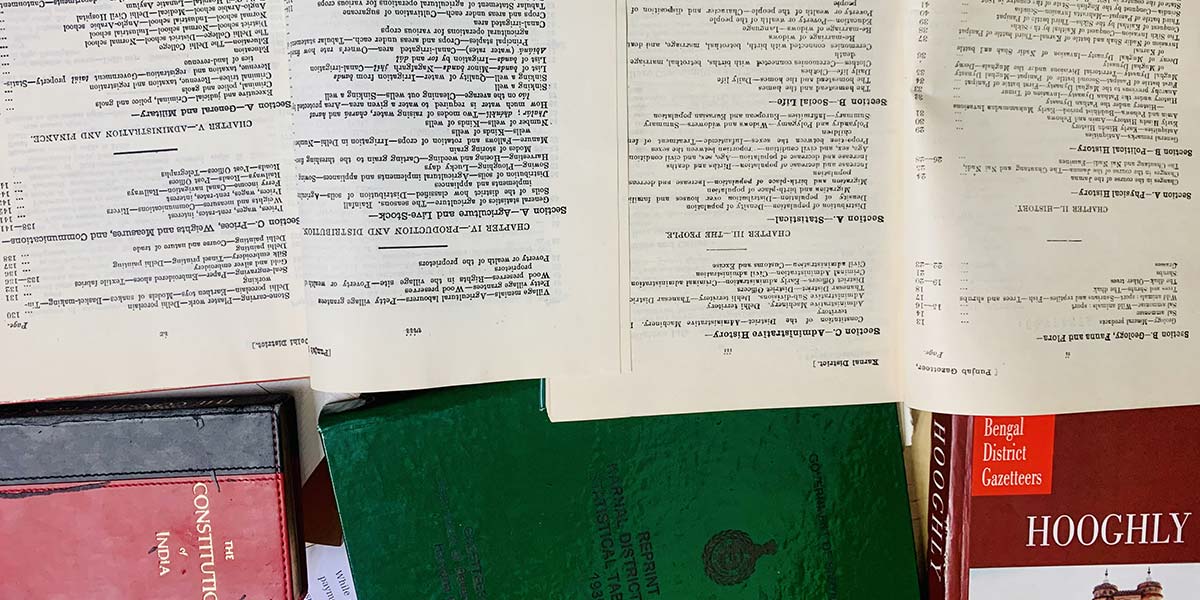

To make sense of the people and place he will now be ruling, he would be handed over a Gazetteer. A Gazetteer could be called an encyclopedia of a place. It contains information about the place, its people, geography and history. It would be like a textual map of its culture and other information important for revenue – surely the British have a ‘burden’ to ‘civilize’ men there and to squeeze their wealth. The Deputy Commissioner reads the gazetteer, and familiarizes himself with the place he must govern. He creates a living imagination of the town.

Gazetteers written in British India are some the most crucial documents of colonial archives history. They were powerful informational devices, that were instrumental to help the British run a country more than 20 times their size (in area) and 8 times their population (around 1900). During the peak of their career (one may say 1891-1921) there were merely 100 thousand British nationals ruling over 300 million Indians (that is 1 British every 300 thousand Indians). This remarkable feat of governance couldn’t have been possible without an excellent inventory of knowledge like Gazetteers that the British created which enabled institutions to grow.

So obsessive was this documentation process of the colonial rulers that earlier British officers were often called Administrator-scholars. Names of John Malcolm, Thomas Munro, Mountstuart Elphinston, James Todd, Colin Mackenzie come to mind, who wrote enormous volumes on India and paved way for a colonial understanding that was to follow for a century ahead.

How did this word, ‘gazetteer’ come about? During the 14th century Italy, when a currency coin named saldo was introduced, two such coins were called as gazetta. Since a newspaper was sold for two saldo, the word gazetta came to signify newspaper. French took the word and made it Gazette. When the Great Plague broke out in London in 1665, Charles II and the Royal Court fled to Oxford. There, they started a newspaper in the new town (people wouldn’t buy one from London for fear of contagion). This newspaper was called the Oxford Gazette, later renamed, London Gazette. This was slightly different from a newspaper – it was an official journal of records and was sold to subscribers only and not printed for general public. The ‘eer’ at the end simply makes it a proper noun. So much for English language!

Anyway, so was it the first such exercise of documenting India? Well, capturing and recording knowledge about culture and geographies was not new to India when British arrived. For instance, part of Abu’l Fazl’s Ain-e-Akbari could be regarded as Gazetteer of the 16th century – throwing light on life and times during Akbar’s reign. Tamil Gazetteers could be traced to Sangam Literature from 200 BCE to 300 CE. Many of our own accounts are historical. For instance, Muhnot Nainsi, the Dewan of Marwar in 17th century wrote about the region of Rajasthan extensively and wrote gazetteers (Marwar Ra Pargana Ri Vigat) for the Marwar region. But by and large, and perhaps because Indian traditions have often been oral in nature, systematically and comprehensively writing works explaining details about the place and people are hard to find.

If one looks at Volume I of the Imperial Gazetteer of India, one cannot help but remain surprised at the sheer ingenuity and comprehensive nature of research done by the British on India (irrespective of whether they captured the nuances, for a late 19th century product, this Gazetteer was impressive). Its table of contents contains chapters on Physical Aspects (valleys of Kashmir, Ganges, Indus, Assam, Burma, Thar Desert, Nilgiris, Cauvery, Ceylon etc.), Geology (pre-Cambrian, Dravidian, Aryan era), Meteorology (climate, draughts, and rainfall), Botany (from Himalayas to Andaman), Zoology (all kinds of reptiles, mammals, birds, fishes that inhabited the subcontinent), Ethnology and Caste (with details of tribes and castes and their theoretical explanation), Languages, Religions, Population and Public Health. This was by no means a small feat with a country, the size of a continent, with people belonging to an entirely new approach to life were being documented.

One is also amazed at the sheer arrogance with which these documents claimed to hold knowledge about India. To be able to carve out ‘truth’ statements about a culture as diverse and as ‘different’ from the writers was an intellectually violent exercise. But then, when is colonization not!

Consider James Mill, father of John Stuart Mill, who was a colonial administrator at the East India Company. He wrote a three-volume book, ‘History of British India’ in 1818, which profoundly influenced British rule and views about India. In fact, it still continues – when we divide India’s history into Hindu, Muslim and British, we are using the categorization that Mill first created.

How many times do you think Mill visit India to write about India?

Zero!

Yugank Goyal teaches at FLAME University and is founding director of the Centre for Knowledge Alternatives. The Centre’s first project is to re-create gazetteers of India.